One rider in two is injured every year throughout the world. This bleak statistic is not improving with time - quite the contrary. So that's a good basis for this article. But rest assured, there are a few points that can help you to see things more clearly.

The crucial element that revolves around an injured rider is usually their lack of understanding of the situation. A lot of thoughts go through their head, and little Jiminy Cricket doesn't often give the best advice.

"It's in your head" "You're in pain, stop everything and don't do anything else" "Running isn't for you" "I don't understand why you're in pain".

The aim of this article is not to provide self-diagnosis or miracle recipes. The aim is to raise awareness so that you can quickly activate the levers to prevent an injury from becoming a major factor in your life.

The case of X

But first, I'd like to share the case of X, a cliché, but one that, I assure you, is not uncommon.

X, who has been running for 4 months, is experiencing pain in the anterior aspect of his left knee. He/she has gradually increased his/her training volume by following a plan found in a magazine. He/she has been slowly building up speed and, for the last 3 weeks, has been increasing the gradient a bit sharply. Yes, he/she is training to complete his/her first short-distance trail (25km, 1500 D+).

This pain progressively worsens as he/she goes on outings with long downhill sections at a rate of 4x/week.

Her running partner, Y, tells her that he/she has already had this problem and explains everything that he/she has done to treat it. Y even ventures to tell her that she suffers from patellofemoral syndrome.

With this in mind, X did a vast amount of research on the internet to find out what it is and what really needs to be done. With her race just 2 months away, X was determined to do everything in her power to make the pain go away! Alas, what had to happen happened: a host of information turned his head, adding a dose of stress: ice, rest, anti-inflammatories, physio, surgery, orthopaedic insoles, changing shoes, stopping running for good or continuing without straining, straining, not listening, etc, etc. In fact, everything and its opposite.

He/she decides to go and see his/her doctor, who confirms what he/she has found on the internet. The tragedy was that this goal meant a lot to X and the idea of not being able to take part made him/her feel bad. The doctor prescribed physiotherapy and anti-inflammatories and suggested that he/she stop running for 6 weeks. Which he/she did.

After 6 weeks, the pain was gone. X therefore resumed running, gradually. He/she skipped his/her trail race, but decided to set a new goal 1 month later. There was a significant increase in the altitude difference, and boom: the pain returned. The only thoughts that cross X's mind are incomprehension, sadness and anger. All emotions that are not worthy of a pleasurable sporting experience.

This case is certainly a cliché, but it's the story of many patients. Unfortunately, we have to admit that, at the present time, treatment is not working well for many people.

Most of the time, there is a lack of common sense when it comes to dealing with these issues. We tend to get lost in complex approaches to most situations, based on unfounded beliefs and reinforced by deep-seated myths.

Discuss, explain and analyse: this is the basis of treatment. Understand the pain mechanism and target the cause. There will almost always be a change in the runner's habits: more speed, more volume, a change of equipment. This is the loading principle. This principle should be correlated with capacity, i.e. the runner's ability to bear the load. Great fatigue at work or at home, intense stress, poor sleep or health problems affect this capacity. This is why certain overload or repetition pathologies also appear when no change has been made to the runner's training habits.

So when loads occur too quickly and too strongly for the body's tissues, or the runner's capacity decreases, the tissues end up becoming irritated. This is known as overload or repetition injury. From there, there are a few fundamental principles to help cure a pathology.

What can be done?

When pain occurs, listen to it and immediately try to understand why it is there. Reduce the load a little until the problem passes, then gradually return to the intensity you expected. If this doesn't work in the very short term, consulting a health professional will help diagnose the condition in question. This diagnosis will lead to the right treatment and adaptation, so that the pain passes and the structures are strengthened. And the 80% of the work will be done via Mechanical Stress Quantification.

Quantifying Mechanical Stress

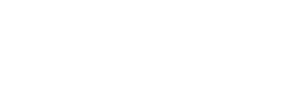

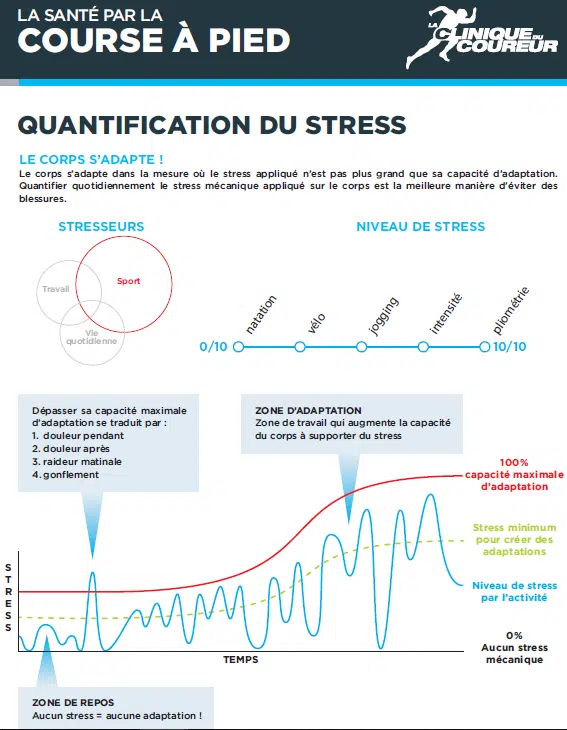

Pain often occurs when the tissues' maximum capacity for adaptation is exceeded. This maximum capacity (red line) fluctuates more or less over time, depending on our state of fatigue, stress, etc.

Regularly exceeding this maximum capacity for adaptation weakens structures and makes the body's tissues less and less tolerant of stress. This is the misadaptation. Basically, the rider doesn't listen and pushes.

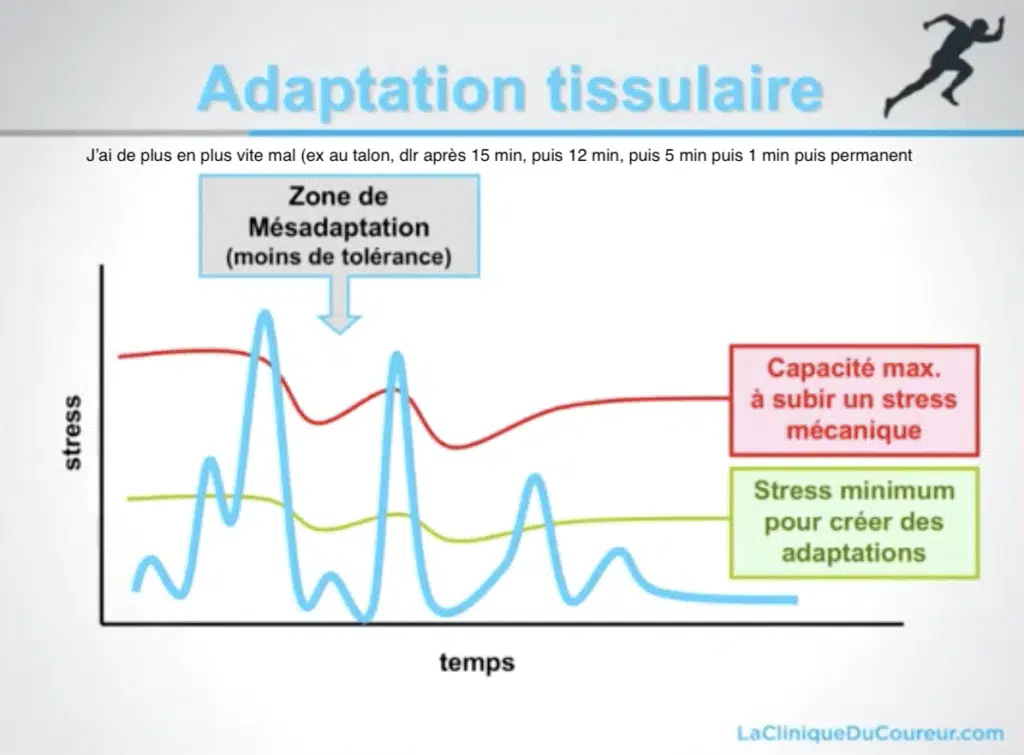

Strict rest, where the maximum constraints would be, for example, going shopping and taking a digestive walk around your house, also weakens the structures. This is the maladjustment. Basically, the rider does nothing more

The aim of QSM is to gradually increase the load by providing sufficient stimulation, with the aim of strengthening, but without exceeding what the body can tolerate. The aim is to avoid generating irritation and, consequently, pain.

"The body adapts insofar as the stress applied is no greater than its capacity to adapt".

To get through this process, all you need to do is listen to the symptoms. Pain (or oedema) during an effort, but also afterwards and/or the following day, is a sign that you have crossed the red line. You should therefore reduce your next load a little to find the right dosage at the right time, so that you are just under the red line. Very gradually increasing the load as you go along will, in the right dosage, strengthen the body and push that limit higher and higher.

It is important to remember that in older injuries, the pain signal alone is not a good indicator of progress. In the case of chronic injuries, it is often permissible to carry out an activity with moderate pain (1-2/10), on the sole condition that the pain does not increase in the 24 hours that follow and that it is possible to carry out the same training the next day.

This notion also applies to preventive measures, as part of the business recovery process.

Load, repetition, amplitude

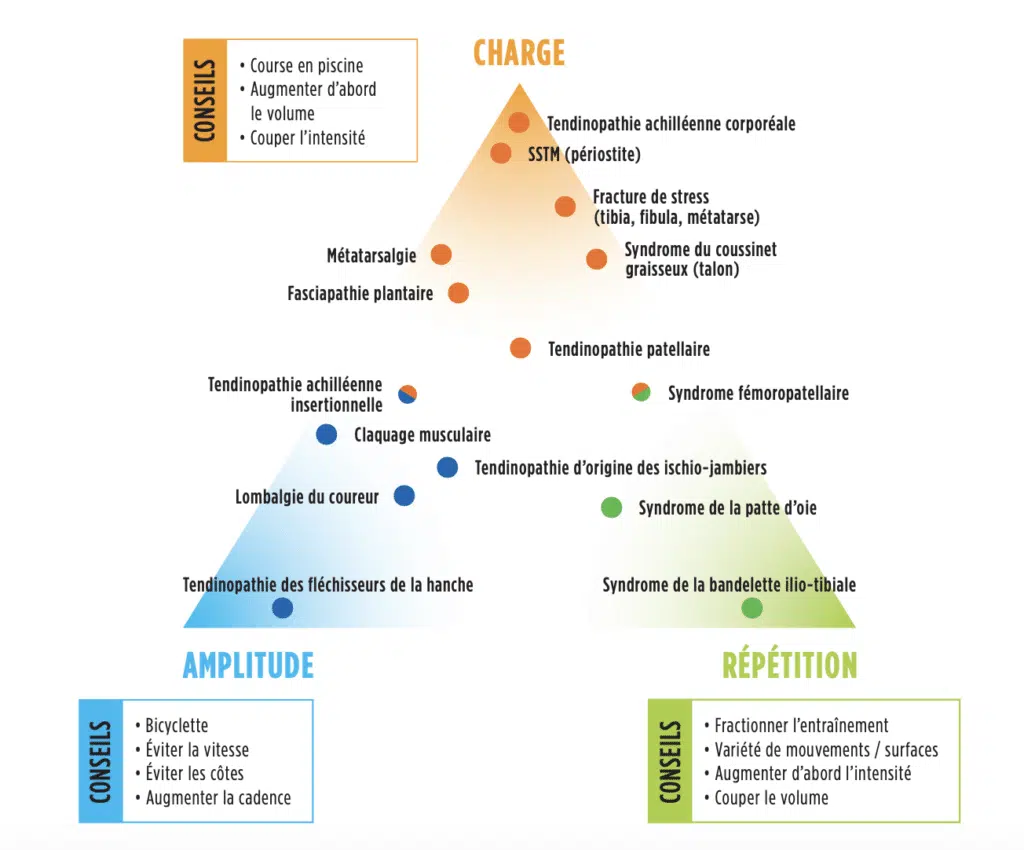

Establishing a diagnosis will also make it possible to better quantify mechanical stress by adapting running effort, minimising the risk of causing irritation and improving QSM advice. Schematically, there are 3 classes of pathologies: load, repetition, amplitude.

Management of a weight-bearing pathology will focus on reducing the intensity of training. At the start, it's a good idea to keep your EF outings quiet, flat and not long. Then gradually increase the volume, and eventually the speed (and the altitude difference). Compensating for the reduction in training with a load-transfer activity is an important parameter (cycling, swimming).

Management of a repetition pathology will focus on reducing the volume. You can nevertheless maintain intensity by splitting your outings (twice a day). Fractional training can also be achieved by alternating walking and running. An important point with this type of injury is to vary the surfaces and footwear as much as possible.

Managing a pathology of amplitude means reducing the difference in altitude (especially on descents), reducing speed and maintaining a high volume of hilly EF with a high cadence. Transfer activity is also important!

And what about the speed of the impact force?

Let's not dwell on this subject for too long, as it could be the subject of an entire article on its own. But when it comes to managing an injury, taking an interest in the speed of the foot's impact on the ground is an important element, with the aim of reducing the stress on an injured area. Scientific studies are unanimous: the greatest source of injury is the speed of impact. impact force speed (rather the impact force application rate or Vertical Loading Rate). Adopting the right impact moderation behaviour will enable you to maintain your effort while minimising the stress on certain areas of the body. This can easily be achieved by working on the stride, with a fairly high cadence (scientifically, we're talking about 180 steps per minute +/- 15). Quite often, simply focusing on the noise of the impact allows you to be in this protective cadence zone with a reduced impact force speed. Making less noise is a simple, non-invasive biomechanical change that produces spectacular results.

As you will have realised, nothing is obvious when there is an injury. Taking the symptoms seriously as soon as possible seems to be a good first step. If these don't improve very quickly as a result of self-adaptation, consulting a health professional who is familiar with proven therapeutic approaches is the best option for optimal recovery in the short and long term, without getting bogged down in complex, costly procedures that offer no guarantee of a favourable long-term prognosis.

But the bottom line is to avoid getting to that point, and there are ways of avoiding all that hassle: run regularly, gradually and with motivation!