One out of every two runners is injured every year worldwide. This dismal statistic does not improve with time, quite the contrary. That’s how we set the scene for this article. But don’t worry, there are a few points that can help you see things more clearly.

The crucial element revolving around an injured rider is usually his or her lack of understanding of the situation. Many thoughts cross their minds, and little Jiminy Cricket doesn’t often give the best advice.

“It’s normal to be in pain, you have to exert yourself” “It’s in your head” “You’re in pain, stop everything and do nothing more” “Running isn’t for you” “I don’t understand why you’re in pain”.

The aim of this article is not to provide self-diagnosis and miracle recipes. But to create an awareness that can quickly activate levers, so that an injury does not become an important parameter in life.

The case of X

But first, I’d like to share the case of X, a cliché but, I assure you, a common one.

X, who has been running for 4 months, feels pain in the anterior aspect of his left knee. He/she gradually increased his/her training volume by following a plan found in a magazine. He/she has been slowly building up speed and, for the past 3 weeks, has been increasing the gradient a little abruptly. Yes, he/she is training to complete his/her first short-distance trail (25km, 1500 D+).

This pain progressively worsens as he/she goes on outings with long descents at a rate of 4x/week.

His/ her running partner, Y, points out that he/she has already had this problem and explains everything he/she has done to treat the boo-boo. Y even ventures to tell her that she’s suffering from patellofemoral syndrome.

With this in mind, X carried out an extensive internet search to find out what it was and what really needed to be done. Her race is in 2 months, and X is motivated to do everything in her power to make the pain go away! Alas, what had to happen happened: a host of information turned his head, adding a dose of stress: ice, rest, anti-inflammatory medication, physio, surgery, orthopedic inserts, shoe changes, stopping running for good or continuing without forcing, forcing, not listening, etc, etc, etc. In fact, everything and its opposite.

He/she decides to go and see his/her doctor, who confirms the internet findings. The tragedy is that this goal meant a lot to X and the idea of not being able to take part makes him/her feel bad. The doctor prescribed physiotherapy and anti-inflammatories, and suggested that he stop running for 6 weeks. What he/she does.

After 6 weeks, the pain is no longer present. X gradually resumes the race. He/she skips the trail, but decides to set a new goal 1 month later. The ascent is significant and boom: the pain returns. The only thoughts that cross X’s mind are incomprehension, sadness and anger. So many emotions that are not worthy of a pleasurable sport.

This case is certainly a cliché, but it’s the story of many patients. Unfortunately, we have to admit that, at present, many people are not well taken care of.

Most of the time, there’s a lack of common sense when it comes to dealing with these issues. We tend to get lost in complex approaches to most situations, driven by unfounded beliefs and reinforced by deep-seated myths.

Discussing, explaining, analyzing: this is the basis of care. Understand the pain mechanism and target the cause. There will almost always be a change in the rider’s habits: more speed, more volume, a change in equipment. This is the charging principle. This principle is correlated with capacity, i.e. the rider’s ability to bear the load. Fatigue at work or at home, intense stress, poor sleep or health problems all affect this ability. This is why certain overload or repetition pathologies also appear when no change has been made to the runner’s training habits.

So when loads come on too fast and too hard for the body’s tissues, or the runner’s capacity diminishes, they end up getting irritated. This is known as an overload or repetition injury. From there, there are a few basic principles to help cure a pathology.

What can we do?

When pain occurs, it’s time to listen to it and immediately try to understand why it’s there. Reduce the load a little until the problem passes, then gradually build up to the desired intensity. If this doesn’t work in the very short term, consulting a healthcare professional will help diagnose the pathology in question. This diagnosis will lead to the right treatment and adaptation, so that the pain passes and the structures are strengthened. And 80% of the work will be done via Mechanical Stress Quantification.

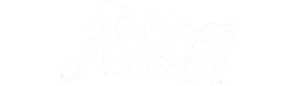

Quantifying Mechanical Stress

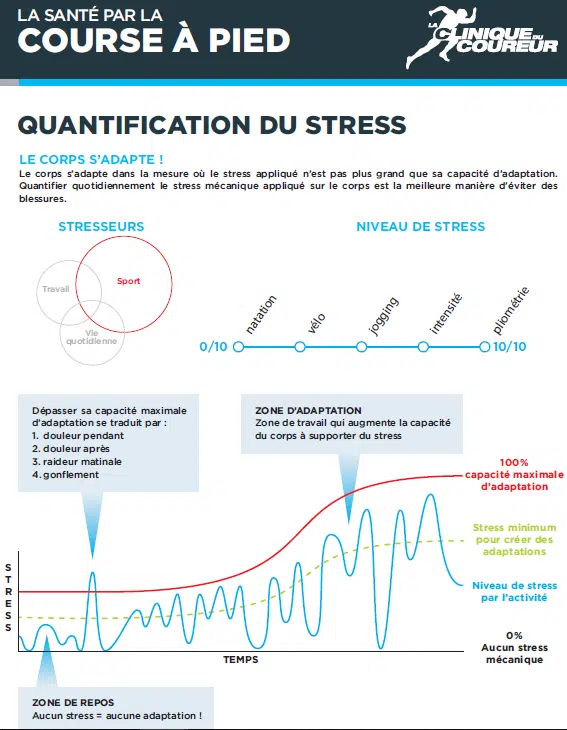

Pain often occurs when the tissues’ maximum capacity for adaptation is exceeded. This maximum capacity (red line) fluctuates more or less over time, depending on our state of fatigue, stress and so on.

Regularly exceeding this maximum capacity for adaptation weakens structures and makes the body’s tissues less and less tolerant of stress. This is the maladaptation . Basically, the rider doesn’t listen and pushes.

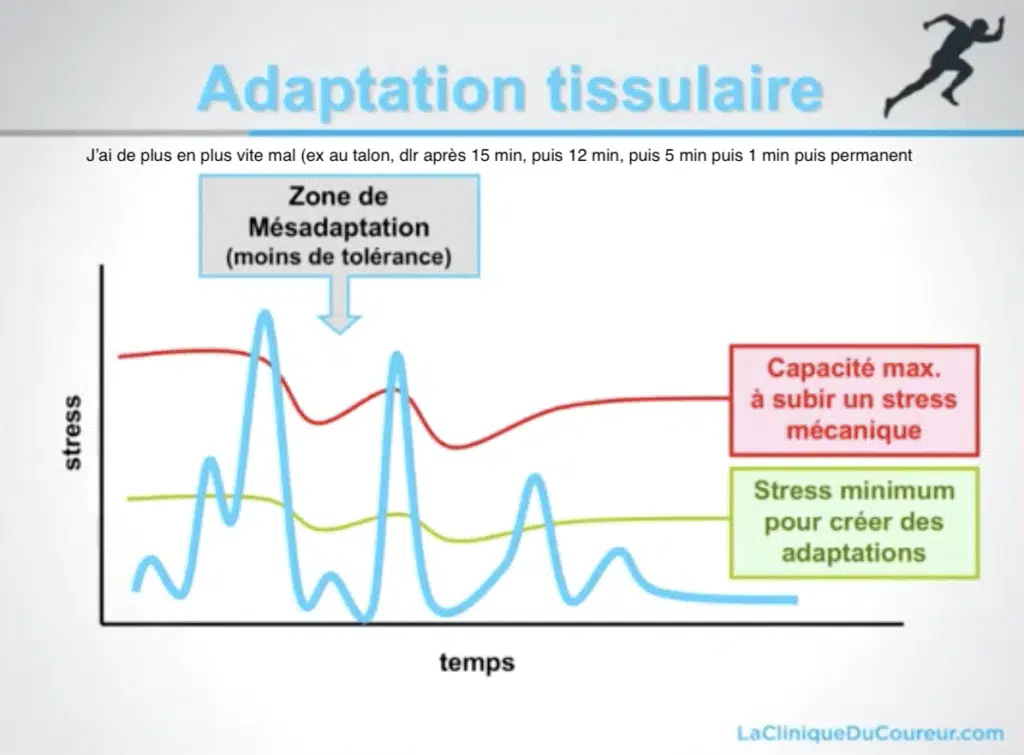

Strict rest, where the maximum constraints would be, for example, going shopping and taking a digestive walk around your house, also weakens structures. This is maladjustment . Basically, the rider does nothing.

The aim of QSM is to gradually build up the body’s capacity for action, through sufficient stimulation, without exceeding what the body can tolerate. This is to avoid generating irritation and, consequently, pain.

“The body adapts insofar as the stress applied is no greater than its capacity to adapt.

To make the most of this process, you simply need to listen to your symptoms. Pain (or oedema) during an effort, but also afterwards and/or the following day, is a sign that this red line has been crossed. So you’ll need to reduce your next load a little to find the right dosage for the moment, which will enable you to be just below this level. Gradually increasing the load will, in the right proportions, strengthen the body and push the limit higher and higher.

It’s important to remember that in older pain conditions, the pain signal alone is not a good indicator of progress. In the case of chronic injuries, it is often permissible to carry out an activity with moderate pain (1-2/10), on the sole condition that the pain does not increase over the following 24 hours, and that it is possible to carry out the same workout the following day.

This notion also applies to preventive measures, as part of the recovery process.

Load, repetition, amplitude

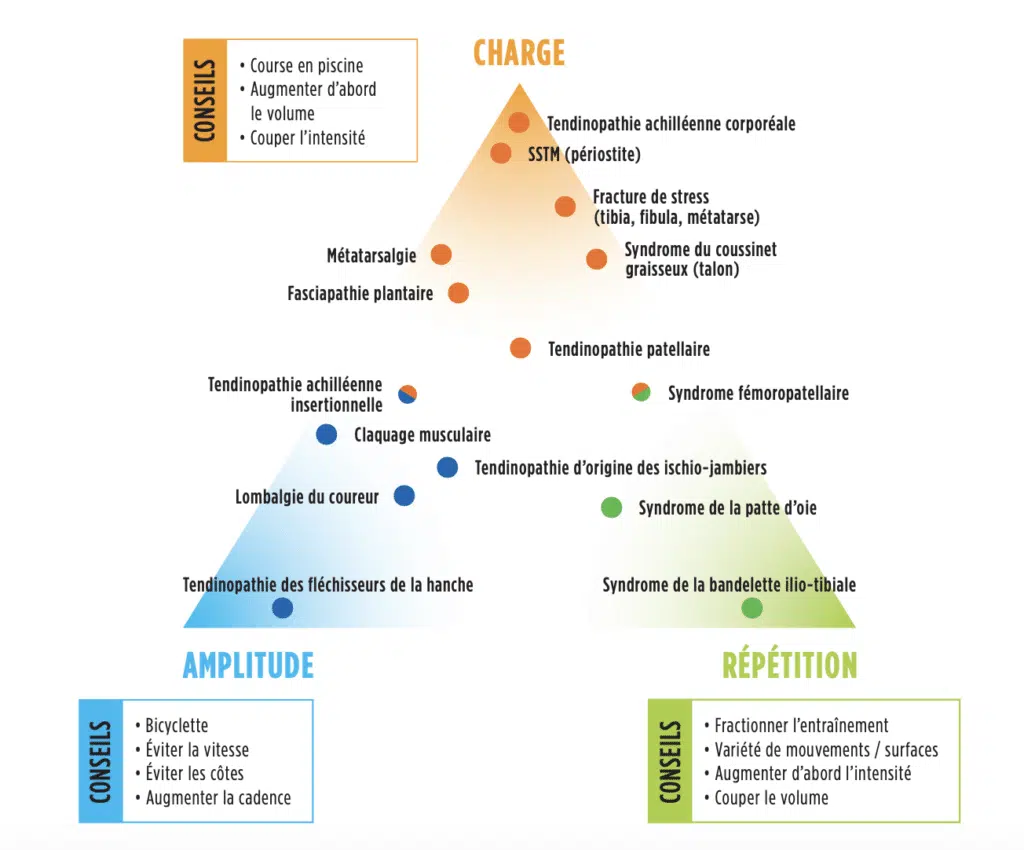

Diagnosis will also enable us to better quantify mechanical stress by adapting running effort, minimizing the risk of irritation and improving QSM advice. Schematically, there are 3 classes of pathologies: load, repetition, amplitude.

The management of a weight-bearing pathology will focus on reducing the intensity of training. In the early stages, it’s a good idea to keep your EF outings short and flat. Then gradually increase the volume, and at some point the speed (and elevation gain). Compensating for reduced training with a load-transfer activity is an important parameter (cycling, swimming).

Management of repetitive pathology will focus on volume reduction. However, you can keep up the intensity by splitting up your outings (twice a day). Alternate running and walking. An important point with this type of injury is to vary surfaces and footwear as much as possible.

Managing a pathology of amplitude means reducing the difference in altitude (especially on descents), reducing speed and maintaining a high volume of hilly EF with a high cadence. High transfer activity too!

And what about impact force speed?

Let’s not dwell on this subject for too long, as it could make an entire article in itself. But when it comes to managing an injury, focusing on the speed of the foot’s impact on the ground is an important element, with the aim of reducing stress on an injured area. Scientific studies are unanimous: the greatest source of injury is the speed speed of impact force (or rather the Vertical Loading Rate). Adopting the right impact moderation behavior will enable you to maintain effort while minimizing stress on certain areas of the body. This can easily be achieved by working on the stride, with a fairly high cadence (scientifically, we’re talking about 180 steps per minute +/- 15). In many cases, simply focusing on the sound of the impact can bring you into this zone of protective cadence at a reduced impact force velocity. Making less noise is a simple, non-invasive biomechanical change that produces spectacular results.

As you can see, nothing is easy when there’s an injury. Taking symptoms seriously as soon as possible seems a good first step. If these are not rapidly reduced by self-adaptation of one’s practice, consulting a healthcare professional who is familiar with proven therapeutic approaches is the best option for optimal healing in the short and long term, without getting lost in complex, costly procedures that offer no guarantee of a favourable long-term prognosis.

But the bottom line is to avoid getting there, and there’s a way to avoid all that hassle: run regularly, progressively and with motivation!